Don Pedro Esteva is currently serving a second term as President of the Dominican Republic’s Chamber of Mining and Petroleum (CAMIPERD). A third-generation leader at IMCA (and preparing the fourth), he is a discreet man who rarely speaks publicly.

And when he does, it’s usually to talk about something he is passionate about: technical education.

—We’ll talk about education, but first… what’s the biggest issue the mining sector is facing today?

I think the biggest issue is that exploration is a critical part of mining, and from the moment prospecting begins until a mining operation is up and running, it can take ten to fifteen years. There’s a lot of trial and error involved.

Of course, the National Geological Survey provides historical data about areas that may show what miners call “anomalies.” Only after further exploration can mineral deposits be confirmed.

—But…?

But right now, permits for exploration are being granted very slowly, especially environmental permits. There aren’t enough companies exploring to ensure that, ten to fifteen years from now, the country continues to receive income from mining.

—Has this permit slowdown been an issue for a while, or is it more recent?

There’s something fundamental involved: the terms of reference that must be issued by the Ministry of the Environment for proponents to obtain an exploration permit. The environmental impact study must be based on these terms of reference.

—But the ministry isn’t issuing them?

Recently, the Ministry of the Environment issued a resolution that centralized this process within the Ministry itself—before, it required the explicit approval of the President of the Republic.

—So those permits used to come straight from the Presidential Palace.

Exactly. Not anymore. Now, with this resolution, the Ministry of the Environment handles it directly. This is the case for the permits related to the Romero Project operated by GoldQuest and the gold and copper mine in Dajabón operated by Unigold.

—What’s CAMIPERD’s view on the creation of a public mining company?

It’s a positive step that Emidom was created, because its first task has been to speed up the exploration process.

—So, you’ve benefitted indirectly…

Definitely, because now the Dominican government itself is involved, recognizing the importance of exploration in determining whether there’s commercial value in continuing to explore and eventually exploit a deposit.

—How long can exploration for rare earth elements take?

With proper resources, it can be done in a shorter time. That’s the main challenge for junior mining companies that come to explore. These junior companies are focused solely on exploration.

They don’t go on to exploit because their goal from the beginning is to raise venture capital—say, 40 or 50 million dollars—explore, and once they’re certain there are promising mineral quantities, they sell the project to a larger company that has the capital and expertise to develop the mine.

—Will this new public mining company need knowledge transfer from private companies?

I imagine so, because the Dominican government lacks exploration experience. That’s why they’ve brought in experts from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and other international institutions.

—How does CAMIPERD view U.S. involvement?

The Dominican Republic has Chinese, American, Canadian miners… there’s no problem with that.

—Are some projects halted due to fear of environmental activists?

That’s a poorly resolved conversation. I believe the President is very sensitive to environmentalist opinions and gives them the attention they deserve—because, in the end, we all want to protect the environment.

What I think is that the conversation with those who have such concerns should seek balance with those looking to develop mining, agricultural, industrial, or tourism projects. However, I believe scientific rigor should prevail.

—Companies talk about responsible mining. But… is that enough?

From a mining standpoint, yes, mining is sustainable. Why? Because it must first bring fiscal benefits to the country, returns for investors, and quality job creation for people.

According to the Social Security Treasury, mining jobs pay an average monthly salary of about 77,000 pesos. That’s higher than what’s paid in the national financial system, which traditionally has a reputation for good wages.

—Do we have the workforce here, or does talent need to be imported?

Mining involves many sciences, both in exploration and exploitation. Since the first mining concession, Quisqueya I to Falconbridge, several generations of geologists and professionals have emerged.

PUCMM in Santiago even offered a degree in geology and mining. More recently, UTECO, the university in Cotuí, launched a geology engineering program. But there’s still room for better collaboration between industry and academia.

—Does the Chamber work in that direction?

Several Chamber members are involved. Including the company I work for, which has a diesel technician training program. When it comes to mining equipment and its maintenance, we don’t employ foreign technicians.

There has been significant progress in this area—for example, at Barrick, 97% of employees are locals.

—Is mining a very political topic?

Very political, absolutely.

—Which parties support the sector?

I think all parties are fairly aligned with the economic value mining brings to the Dominican Republic.

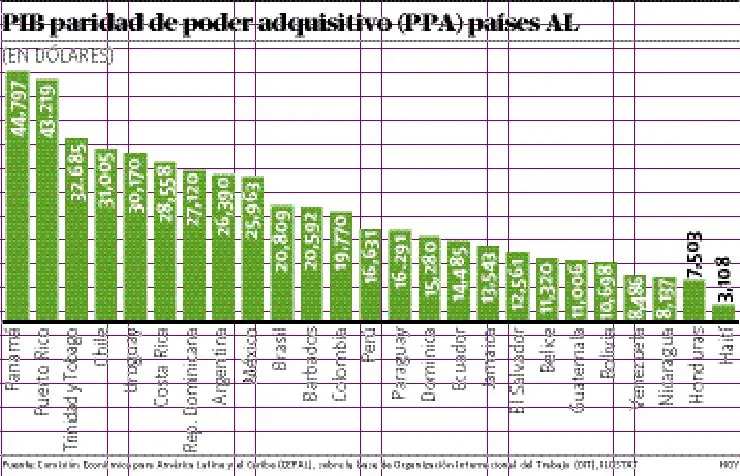

Between 2010 and 2020, mining represented 2% of the GDP—that’s over 2 billion dollars.

—And in taxes?

Last year, about 1.5 billion dollars. And that’s, as we say, all linked. I think we have a tradition of mining in this country, but we haven’t fully embraced it.

That’s unfortunate. Mining involves rigorous science and highly trained people. I think we’re ready to identify the challenges of mining, find ways to mitigate them, and assess the risks.

—What about sand miners and river extractors—are they considered part of the mining industry?

That’s a good question because, like in all industries, there are informal operators. CAMIPERD has nearly 50 members, and each understands the importance of sustainability.

Informals range from people with picks, shovels, and donkeys hauling sand from riverbanks to entrepreneurs with earth-moving equipment who simply operate without permits.

They have no remediation or closure plans in place once the mineral source is depleted.

—And they’re rarely penalized… they just keep going.

I think each ministry needs a better budget to do its job properly. For instance, the Ministry of the Environment needs more resources to ensure that only permitted companies are operating.

—Protests usually target big companies, but they say informal mining is more dangerous and harmful. Is that true?

Yes, absolutely. There’s no doubt. The issue is that informality doesn’t consider sustainability—environmental or human. And fiscally, it contributes nothing because it’s clandestine.

The best-case scenario is strong ministries with adequate budgets to guarantee that mining operations are truly sustainable. There’s a lot of informality right now, especially in non-metallic mining.

Source: